In the first two essays, I explored Ajé as worldview and as moral economy. Now, I turn to the marketplace, the cultural and institutional home of Ajé in Yoruba life.

First, let me restate that Ajé is the animating, generative force of wealth and exchange. It is more than money.

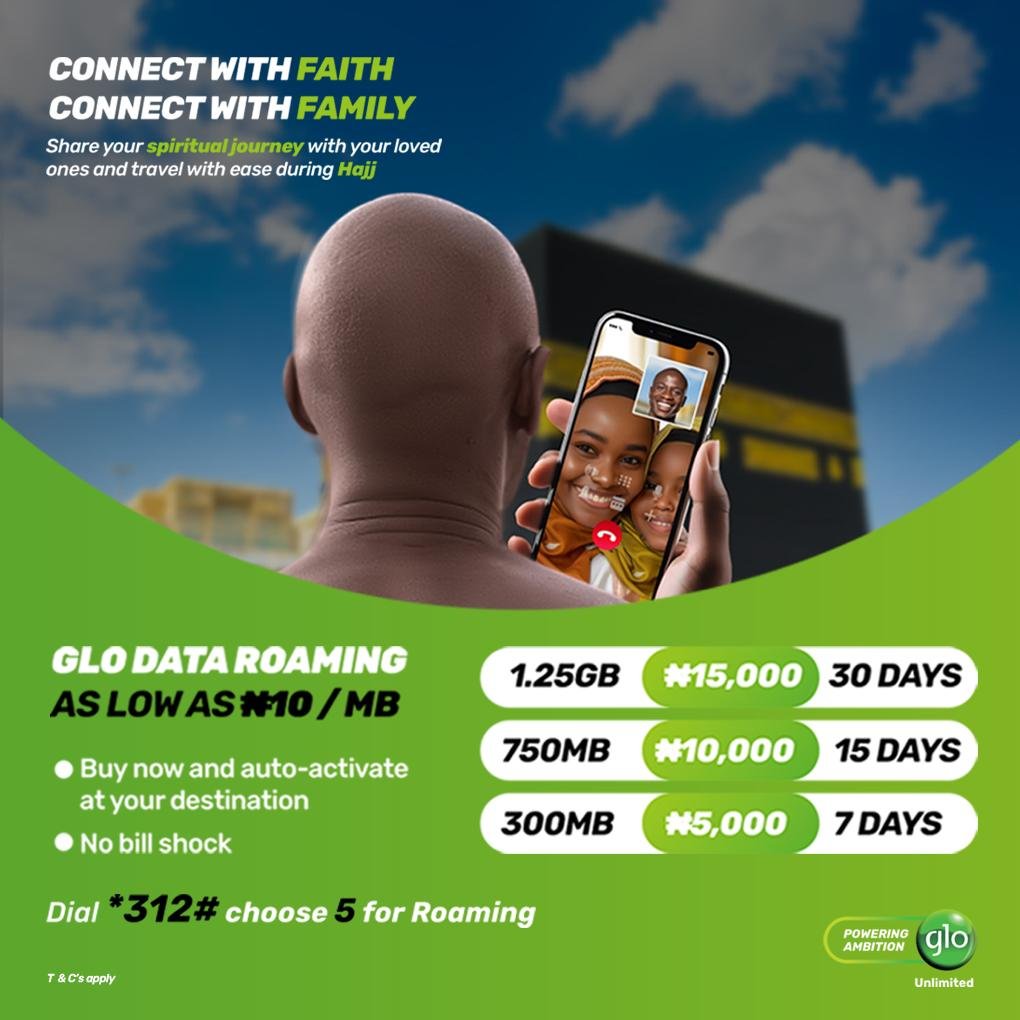

A few years back, I picked up an artwork (image attached). I was drawn to it for its simple message: the presence of women in conversation in the marketplace. It aligns with my belief that women, in a loose sense, ‘own’ markets.

In Yorubaland, the king has jurisdictive ownership of markets, there are in fact several markets designated ‘Oja oba’. Nevertheless, historically, women constitute the majority of people who engage in commerce.

My belief is coloured by my childhood experiences, some of which I captured in my childhood memoir, Memories of Grandma.

I am the grandchild of three women of commerce. I often went with my maternal grandma to the market as she sold her wares, and helped to sell when we returned home.

Her mother, my great grandma was a notable seller of palm wine. She sold in large quantities to retailers, she was a rallying point for men and women, a community leader.

My paternal grandma was an Iyalaje of palm oil sellers in Erunmu. So, I am drawn to markets and its spirit of enterprise.

In Yoruba worldview, the world is metaphorically a market, necessitating the saying, ‘aiye loja, orun nile’. We will eventually exit the world just as we exit a market.

A market, like the world, signifies a temporary gathering point, an interactive space for economic and social negotiation, collaboration, and wellbeing.

Markets were not spaces where women operated on the margins, it is one of the few spaces where men deferred largely to women in leadership, influence, and autonomy.

So, long before formal titles and corporate hierarchies, Yoruba markets recognised women as economic and political authorities.

The role of the Ìyálájé or ìyálọ́jà was never merely administrative. It was a position of immense clout within a structured market governance system. It was usually supported by a board of lieutenants. She regulated prices, mediated disputes, enforced market ethics, reprimanded erring traders, and represented traders in negotiations with political power.

Politicians know this. They court market women as a major power bloc during political campaign, remember that APC’s ‘Trader Moni’ strategy directly targeted markets.

But there has been a flip. Although women historically controlled the flow of Ajé in markets, economic authority has become masculinised in modern narratives of power.

Perhaps, the issue is not that women lacked power, but that we stopped recognising the forms in which it appeared.

I believe this is a direct consequence of colonial disruption and subjugation.

Colonial administration displaced traditional market authority structures where women dominated, to establish formal male-dominated political offices.

Traditional capital and banking services as represented by ‘alajo’ (cooperatives) shifted power from market collectives to isolated, market-independent individuals and power blocs.

Gradually, the associated power of Ajé also moved from market titles to corporate titles. This marked the exit of Ajé from the culturally instituted market space to arenas that limited the visibility and centrality of women.

Thankfully in contemporary times, women are reclaiming and regaining authority in these non-traditional domains of Ajé.

In Nigeria, more women are CEOs of banks, have piloted affairs at the stock exchange and shown leadership as ministers of finance.

Markets are sites of political and community organising. This is where women excelled in the past. Many times, the Ìyálájé and ìyálọ́jà, a variant of Ìyálájé, collaborate to influence communal developments and stability.

Ajé, in this context, operated as a collective force for advocacy and mobilisation. Funmilayo Ransome Kuti strategically mobilising market women against Oba Sir Ladapo Ademola II (the Alake of Egbaland).

In conclusion, I feel men in markets are a minority, even when I know that Ajé is not gendered, and that the office of Babalaje exists in markets in Yorubaland. Ajé, to me, is feminine.

•Fúnké-Treasure is a thinker, strategist and communicator. She is the Convener of the Media Mentoring Initiative Documentary Fellowship for Students.