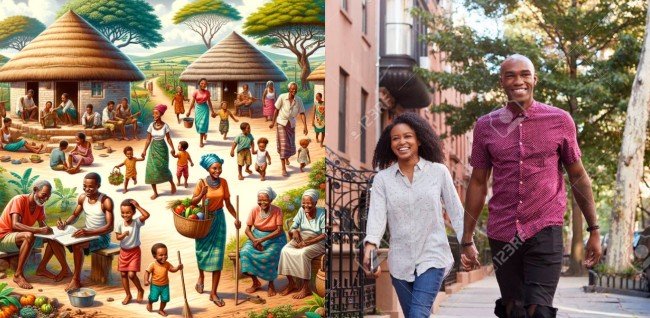

Introduction: As poverty deepens and modernisation spreads, extended family, the traditional African communalism that once sustained generations, faces quiet and gradual extinction in Nigeria. In the traditional African worldview, family is not a closed circle of parents and children; it is a living web of kinship, stretching across bloodlines, villages, and generations.

In Nigeria, communalism has long been the heartbeat of the society, ensuring that no individual is left in isolation. The saying, “It takes a village to raise a child,” is more than folklore—it reflects a philosophy that underpinned our social stability.

In the traditional Nigerian society, the family is not defined by four walls or a surname alone. It is a living, breathing community that extends across generations, cousins, in-laws, and neighbors. This network of shared responsibilities and collective survival is what scholars often describe as the essence of African Communalism.

But, today, poverty and modernisation are eroding the extended family system—leaving Nigerian society to grapple with a quiet social crisis. Today, poverty and modernisation are rewriting the story, leaving both the nuclear family and the essence of communalism in eclipse.

The Extended Family: Heart Of African Communalism

For centuries, the extended family has been the invisible social safety net of Nigerian communities. It ensured that a child without parents could still grow up surrounded by love, and that the sick, the elderly, and the unemployed were never completely abandoned. Births, marriages, and burials were communal events, reinforcing the sense that one’s life belonged to a larger whole.

This system was not merely cultural—it was functional. It absorbed economic shocks, provided emotional support, and preserved intergenerational knowledge. But this safety net, called the extended family, is fraying.

Poverty: Fracturing Bonds Of Kinship

Today, over 60 per cent of Nigerians live in multidimensional poverty. Under such conditions, the extended family—which thrives on sharing—begins to collapse under pressure.

Where once a struggling relative could rely on uncles, aunties, or cousins for support, poverty now makes generosity a luxury. Instead of solidarity, families increasingly experience silent resentment, jealousy, and estrangement.

The age-old proverb, “family is wealth,” now feels aspirational in communities where everyone is barely surviving. Poverty breeds individualism out of necessity, and the extended family suffers first.

Enthronement Of Modernisation And Drift To Individualism

Modernisation has also reshaped family life, gradually enthroning individualism. Urbanisation, western-style education, and migration to cities or abroad have reduced the day-to-day proximity that sustained communal life. The trend is gradually and steadily eclipsing the extended family structure.

In Lagos, Abuja, Port Harcourt, and now fearfully extending to Ibadan and most of the urban areas, especially in Southern-Nigeria, young professionals often live in small apartments, far from their ancestral homes, with limited space or time for relatives. The desire for privacy and independence, amplified by modern living, clashes with the traditional expectations of collective kinship.

Furthermore, technology has replaced physical presence with WhatsApp greetings, and communal visits with cash transfers. While convenient, it weakens the intimacy and shared labour that once defined the extended family system.

Eclipse Of Communalism

When poverty and modernisation converge, they create a society where communalism becomes ceremonial rather than functional. Family meetings are less frequent, cultural rites lose their vigour, and social safety nets shrink. The consequences are visible: rising elder neglect, street children, urban isolation, and mental health crises.

African communalism—built on the extended family—was our indigenous welfare system. Its quiet and gradual eclipse leaves a vacuum that neither government, nor modern life can adequately filled.

Reclaiming Communal Values In A Changing Nigeria

The question, then, arises: how can Nigeria preserve the extended family, the essence of communalism, in a rapidly modernising society?

Nigeria must reimagine how to sustain communal values in a modern context. The pathways include, but not limited to the following:

•Community Empowerment: Supporting local cooperatives and community-based organisations that revive collective responsibility. Urban policies should encourage community centres, cooperative housing, and social projects that can recreate a sense of belonging. All of these can help to strengthen local communities.

•Economic Empowerment: Reducing poverty through targeted social welfare and employment schemes will free families to support extended kin again.

•Social Welfare Programmes: There should be state interventions to assist vulnerable households can reduce the burden that currently overwhelms extended families.

•Cultural Reorientation: Schools, religious bodies, and media should be encouraged to promote the values of extended kinship and empathy that once defined African life. These can revive the values of empathy, shared responsibility, and respect for elders—pillars of the extended family, may African communalism.

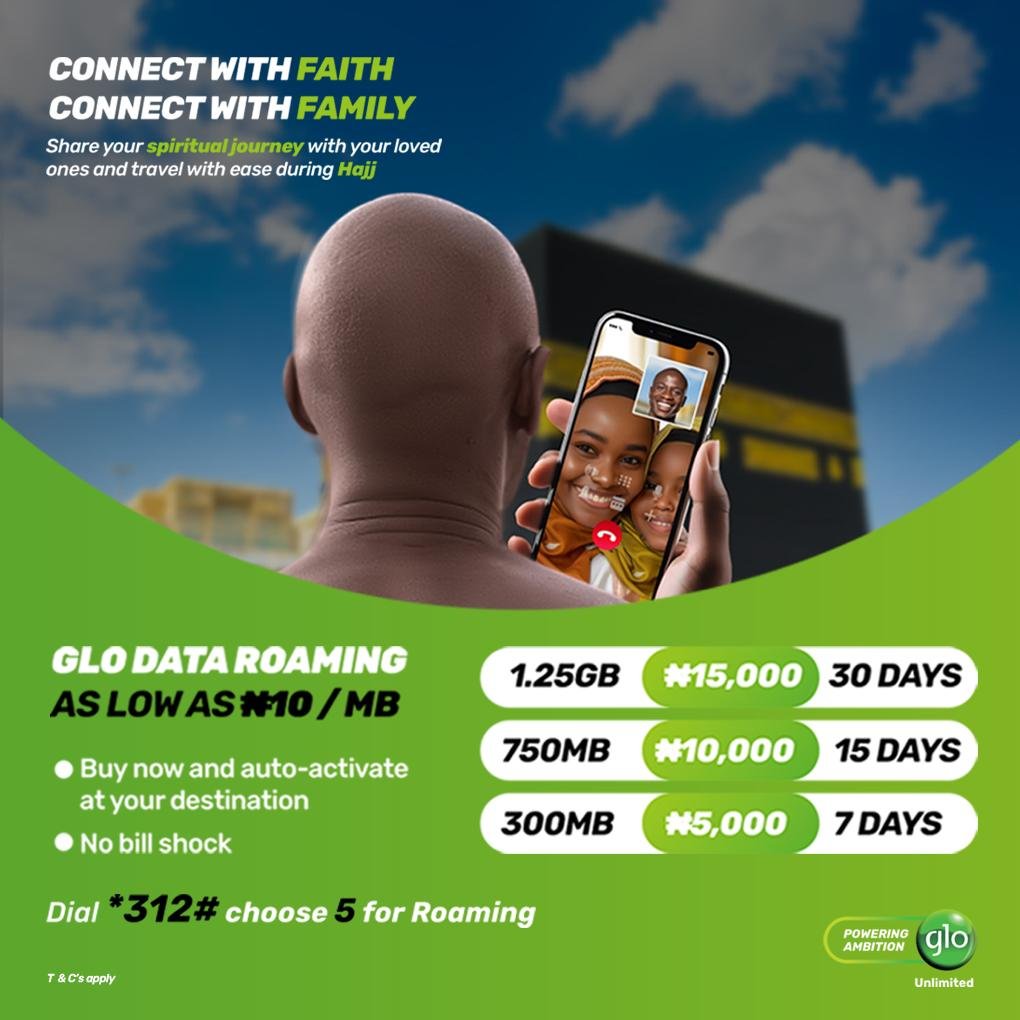

•Leveraging Technology For Community: Digital platforms can be used, not just for greetings, but to coordinate collective support and family projects.

Conclusion

Modernisation does not have to mean alienation. By blending traditional communal values with the realities of nuclear living, Nigeria can achieve a form of modernity that nourishes, rather than fractures, its social fabric.

Nigeria stands at a crossroads where poverty and modernisation threaten the twin pillars of its social life: the nuclear family and African Communalism. Poverty and modernisation are rewriting Nigeria’s family story, slowly eclipsing the extended family and the essence of African communalism.

If nothing is done, the extended family, the social safety net that has sustained generations will disappear, leaving a harsher and lonelier society behind. If left unchecked, the disintegration of these structures will deepen social isolation and weaken our collective resilience.

But by consciously integrating the wisdom of the past with the needs of the present, we can build a future where no Nigerian family—nuclear or extended—stands alone. The challenge before us is clear: to adapt the extended family and cherished communal values to a modern Nigeria without allowing them to fade into nostalgia.