“Therefore, before I proceed to the three arguments that will shape my talk, let me attend to the big elephant in the room. This will also serve as an entrance to the substance of my presentation on the history of Yoruba cosmopolitanism: Ile-Ife, Oyo, and Osogbo.”

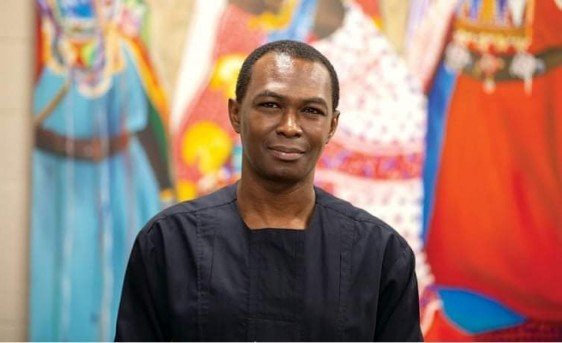

Let me start by thanking the Faculty of Arts Lecture Committee, chaired by Professor G. O. Adekanmbi, for organising this event. My special gratitude goes to Professor Rasheed Olaniyi, Dean of the Faculty of Arts, University of Ibadan, who granted me the honour to address this august body of scholars, staff, students, and members of the public, and gentlemen and ladies of the press.

I also want to thank the Faculty of Arts for recently honouring me with a Distinguished Alumnus Award under the leadership of Dean Emeritus, Professor Solomon Oyetade, who is also chairing this event on behalf of the Vice Chancellor.

I had the pleasure of meeting with the Vice Chancellor, Professor K. O. Adebowale, earlier today. I want to express my gratitude to him for warmly welcoming me back to our alma mater.

I thank my home department—Archaeology and Anthropology— for coming out with full force to honour one of their own. I thank you all for coming from far and near.

I will take one or two minutes to acknowledge that some of the ideas I will share with you this afternoon originated from my conversations with several scholars over the years, sometimes through the collaboration on the books I have edited or co-edited, and through collaboration with colleagues and students on some of my primary research projects.

It was one of those instances of collaboration that brought me into contact with then Mr. Olaniyi, while he was nearing the completion of his PhD. I was working on an edited volume that will be a festschrift for Professor Toyin Falola when a colleague told me about this brilliant, emerging scholar who, in his words, “will certainly go places.” So, I reached out to Mr. Olaniyi, inviting him to contribute to the volume. Within 48 hours, I received his positive response. He went on to contribute a fascinating chapter titled “Kano As An Entrepôt Of the Trans-Saharan Trade.”

In explaining the important roles that Kano played in the regional and global commerce between the 14th and 19th centuries, the freshly-minted Dr. Olaniyi introduced the concept of Diaspora to the lexicon of precolonial Nigerian History. Since then, his several publications, including these two books: Diaspora Is Not Like Home: A Social And Economic History of Yoruba in Kano, 1912-1999 (2008); and Migration And Diaspora Identity In Northern Nigeria and Ghana, 1900–1970: Yoruba Citizenship And Belonging (2025), have expanded our understanding of the dynamics of regional migration and Diaspora in African Studies.

Olaniyi’s work represents a departure from the exclusive focus of Diaspora Studies on slavery and the Americas, and instead focuses on the continental aspects of the Diaspora.

His studies demonstrate the intense mobility and cosmopolitan spirit that have shaped Yoruba History since 1900, calling our attention to the complex practices and negotiations of belonging and being in West African history and the nature of multi-sited, multi-religious, and multi-lingual identity that Yoruba social actors have developed over the past 100 years in Hausaland and Ghana, based on respect for their host communities, strategic blending, and tolerance for diversity. While Dean Olaniyi’s work covers the last 100 years of Yoruba History, mine covers 1000 years before 1900.

Argument

I will make four arguments in this presentation:

1. The Ancestral Yoruba developed a cosmopolitan culture in the 11th Century, and this became the template for an autonomous cultural identity that has been eroded by colonialism and the postcolonial state since the late 19th Century. This cosmopolitan culture was defined by polycentric divine monarchy, Orisa epistemology, open, emergent, and compositional ontology, urbanism, and the quest for technological sovereignty. This cosmopolitan quality has implications for reimagining Africa’s futures and the postcolonial state. I will use case studies from Ile-Ife, Oyo, and Osogbo to illustrate this argument.

2. The colonial state and its postcolonial successor are instruments of erasure of indigenous cultures and knowledge within the nation-state. They both have ethnocidal and epistemicidal tendencies.

3. The colonial social science concepts are often inadequate to capture the ancestral African experiences. Therefore, we must be prepared to create new terms in the English and Yoruba languages that are compatible with the experience of our subject. For example, the ancestral Yoruba identity was neither ethnic nor tribal. It was an organic, emergent, and expansive community of practice.

4. Academic historians must rise to their responsibility as custodians of memory and the past, and become more engaged in public discourses by using critical historical thinking to inform debates and policies.

The Nature Of Evidence: Archaeological History

Five Encounters

There is a big elephant in the room that requires my attention. I am aware that this talk is taking place at the very time that many publics are involved in an animating debate over Yoruba identity and over who should be called Yoruba and who should not. The recent debate originated from a bombastic outburst by the office of one of our royal fathers concerning the question of royal superiority.

This is a perennial problem in Yoruba History. It did not begin with colonialism, but our British colonial masters, postcolonial politicians, and the marginalisation of precolonial history in all tiers of the Nigerian educational system. The recent outburst was about the place of Ile-Ife and Oyo in Yoruba History. Therefore, before I proceed to the three arguments that will shape my talk, let me attend to the big elephant in the room. This will also serve as an entrance to the substance of my presentation on the history of Yoruba cosmopolitanism: Ile-Ife, Oyo, and Osogbo.

I begin by drawing your attention to five encounters that spanned 556 years, reported by one Moroccan Berber explorer, three European men —Portuguese, British, and German —and one Sanhaja Berber scholar, all between 1352 and 1908.

The first encounter: when the Berber-Moroccan explorer, Ibn Battuta, visited the Old Mali Empire between February 1352 and December 1353, he was told of a powerful country to the south, which he rendered in his account as Yūfī, a Mandé or an Arabic transliteration of “Ufẹ̀,” the proper name for “Ifẹ̀” in the central Yorùbá dialect. Ibn Battuta’s Malian informants described this country as “one of the biggest countries of the Sudan” and its king as one of the greatest (Levtzion and Hopkins 2000: 287).

The second encounter came from João de Barros, the foremost Portuguese historian of his generation. De Barros reported that the King of Benin sent an ambassador to the King of Portugal in 1540 to explore commercial, cultural, and political relationships between the two sovereigns. In his account of the Benin ambassador’s visit, De Barros left the following statement to posterity:

Among the many things which King D. João learnt from the ambassador of the king of Beny [Benin]… was that to the east of Beny at twenty moons’ journey–which . . . would be about two hundred and fifty of our leagues–there lived the most powerful monarch of these parts, who was called Ogané. . . . [H]e was held in as great veneration as is the Supreme Pontif with us. In accordance with a very ancient custom, the king of Beny, on ascending the throne, sends ambassadors to him with rich gifts to announce that, by the decease of his predecessor, he has succeeded to the kingdom of Beny, and to request confirmation.

To signify his assent, the prince Ogané sends the king a staff and a headpiece of shining brass, fashioned like a Spanish helmet, in place of a crown and sceptre. He also sends a cross, likewise of brass, to be worn round the neck, a holy and religious emblem similar to that worn by the Knights of the Order of Saint John. Without these emblems the people do not recognise him as [a] lawful ruler, nor can he call himself truly king.

Ogane is a Portuguese transliteration of Ọghẹnẹ, which means “a mighty lord.” But this account has a problem: there was no Oghene to the east of Benin. The only mighty lord that the Benin people recognised is Oghoni (now elided as Ooni) of Ife. In Benin’s Edo Language, the king of Ilé-Ifẹ̀ is referred to as Oghene ne Uhe- “Mighty Lord of Ifẹ̀.” The Benin ambassador did not tell the King of Portugal that his mighty lord is east of Benin. He would have referred to Ile-Ife as “the source of the rising sun,” a common reference to Ile-Ife among the Edo and Yoruba people. This reference is also a metaphor for “the source of cultural vitality” and “place of origin”. But De Barros and other historians, after him, erroneously translated “the source of the rising sun” as East.

Third Encounter: Between March and May of 1830, Richard Lander led a British expedition across the Yorùbá country to determine the course and termination of the River Niger. The explorer spent nine days in Ọ̀yọ́-Ilé, capital of the Ọ̀yọ́ Empire. On May 15, he visited the city’s largest daytime market, Ọjà Ayaba, where he came across an object that arrested his attention. He described this object as a “curious and singular kind of stone . . . It consists of a variety of little transparent stones, white, green, and every shade of blue, all embedded in a species of clayey earth, resembling rough mosaic work.” What Richard Lander mistook for a stone is a glass crucible.

Lander not only bought the “stone,” but he also asked the seller(s) questions about its origins. He summed up the response to his inquiry thus: “The natives informed us that it was dug from the earth, in a country called Iffie [Ifẹ̀], which is stated to be ‘four moons’ [sic] journey from Katunga [Ọ̀yọ́-Ilé], where, according to their tradition, their first parents were created, and from whence all Africa was peopled.”

Fourth Encounter: In 1909, German explorer, Leo Frobenius, visited Timbuktu, where he met a Yoruba community—comprising traders and enslaved people—who regaled him with stories about an ancient city filled with numerous treasures. They identified the city as Ile-Ife, where “all their forbears who had descended into the ground had been turned into stone and still had their own heads, each of which bore its own stamp.” They also told him that there is a place called Olokun Grove where he would find so many treasures, including glass beads. Leo Frobenius used that information to locate and visit Ilé-Ifè from 1910-12. He was not disappointed. Ile-Ife would occupy a central place in his ethnographic travelogue, The Voice of Africa, published in 1913.

Fifth Encounter: The Moroccan invasion and defeat of the Songhai Army in 1590-91 resulted in the capture and enslavement of many dark-skinned Muslims from Western Sudan in Morocco and other parts of the Mediterranean.

One of the captives was Ahmad Baba al-Massufi (1556–1627), a Sanhaja Berber writer, scholar, and political provocateur. While he was detained in Morocco, he engaged in debates with other Islamic scholars over the issue of slavery. He fiercely advocated for the end of racial slavery and instead proposed a religion-based slavery. In doing so, he wrote Mi’raj al-Su’ud (“The Ladder of Ascent in Obtaining the Procurements of the Sudan) in 1615, where he classified the “Yorùbá” as among the West African ethnic groups that could be legitimately enslaved because they were nonbelievers (non-Muslim).

This is the earliest written mention of the Yoruba as an ethnonym. As Historian Paul Lovejoy (“Ethnic designations”, “The Yoruba factor”) has effectively argued, this ethnonym in its origin did not refer only to the Ọ̀yọ́-subgroup but to all Yorùbá-speaking peoples. In this particular context, it applies to all believers in the Orisa Religion because Ahmad Baba al-Massufi believed they, on account of their religion, could be enslaved in Dhar al-Islam.

Ile-Ife: The Genesis Of A Cosmopolitan Identity

These five stories of encounters offer us an entry into the House of Ife (Ile-Ife) and Yorubaland— the Orisa territory. They provide evidence for the place of Ile-Ife in the consciousness and imagination of places inside and outside the Yoruba-speaking world between the 14th and 19th centuries. Every community or society, irrespective of time or place, must decide how it wants to be governed, who it wants to live with, and how it wants to live.

Evidence from historical linguistics points to the western side of the Niger-Benue Confluence as the origin of the Yoruba-speaking peoples. It was here that the ancient proto-Yoruboid Language began to develop ca. 2500 BC. Between 300 BC and 300 AD, this ancient language began to split into different dialects, and the geographical range of the descendant Yoruba, Itsekiri, and Igala speakers expanded from the Confluence to the Atlantic Coast. As proto-Yoruba-Itsekiri speakers expanded, they met and intermarried with prior settlers in the rainforest and woodland savanna. By 700 AD, they had begun to develop a new method of governance based on the idea of divine kingship.

Although the historiography has privileged Ilé-Ifẹ̀ as the source of divine kinship in the Yoruba-speaking world, I have argued elsewhere that Ilé-Ifẹ̀ was not the first place in the region where the idea, practice, and institution of divine kingship developed. In fact, this mode of governance originated in the Ekiti-Igbomina area between 700 and 900 AD. Ilé-Ifẹ̀ was one of the last of the first-generation Yoruba speaking polities to adopt this political system. Nevertheless, it was in Ilé-Ifẹ̀ where the idea of divine kingship received the most coherent ideological and philosophical framework and where the materialisation of this ideology was fully defined.

Securing Yoruba Cosmopolitan Futures With Technological Sovereignty In The 11th Century

After going through a turbulent transition into the divine kingship/urban dyadic configuration at the end of the 10th Century CE, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ became the most ardent promoter of this vision of governance. It was there that a coalition of leaders thoroughly worked out a coherent ideology and intellectual framework for divine kingship. One dimension of this framework was the creation of a myth of origin that transformed Ifẹ̀’s early political leaders into the same category as the leaders of the cosmos.

Although the early development of the kingship institution had begun in Igbomina-Ekiti region before the emergency of Ilé-Ifẹ̀, the leaders of the fledgling city proclaimed that the very idea of divine kingship and urbanism originated from them. They also reorganised the pantheon of the city’s deities, making it universal, so that the city is referenced in traditions as, not only the birthplace of divine kingship, but also as the place where the earth, the first human society, the first king, and the first city were created. And, it is also the place where everyone would eventually return after physical death.

In other words, the intellectuals of Ile-Ifẹ̀ created a new social time that defined their city as the beginning and end of time while also proclaiming their kingship as a universal monarchy and their city as the centre of the universe. Why were they so successful in doing this?

They were successful because Ilé-Ifẹ̀ became the primary source of the materials for legitimising this new brand of divine kingship. Prior to the 11th Century, the most acceptable accoutrement for divine kingship consisted of conical crowns, necklaces, bracelets, and anklets made with red chalcedony beads. These stones were rare in WLN and were imported from the upper areas of the River Niger (e.g., Birnin Lafiya; see Fig. 2.1). Their external origins translated into limited supplies. The more of these beads worn by political office holders (especially kings), the more the splendor and divine grace they were believed to possess.

In what appears to be a determined quest to “re-write” the rule of kingship institution and make itself the centre of social order in the WLN, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ did the unprecedented. It began to manufacture glass, using a unique recipe that consisted of pegmatite (a type of quartz) as the primary raw material. This process may have originated by accident (e.g., during the course of iron smelting), but the genius(es) of this invention recognised its potential, refined it, and began to utilise this glass to create a diverse range of beads.

By including snail shells and other sources of lime (terrestrial and aquatic) in the recipe, the glassmakers significantly lowered the melting temperature for the pegmatite. For colourants, they used cobalt (for blue beads, ṣẹ̀gi) and copper and iron (for red beads, iyùn). They made beads in other colours, including yellow and green. A vast industrial centre, now known as Igbó Olókun, was established in the northernmost part of the city. It was dedicated mainly to glass production.

Igbó Olókun has been the focus of archaeological investigation for over five decades and even much longer by antiquarians. However, only in the last 10 years have the most significant findings emerged from this site, based on the study led by an alumnus of this university, Dr. Babatunde Babalola, and for which he has been awarded the Dan David Prize, the largest prize money for historical research in the world. I estimated that the industrial site occupied about 268 hectares, and that billions of glass beads would have been produced during the 400 years this industrial site was in full operation.

Igbó Olókun was under the king’s control, and he appointed a high-ranking official, Ọwàlódè, to manage and supervise the activities there. This title is still important today in Ifẹ̀ royal coronation rituals. It also appears that in the later history of the region, especially in the 10th Century, a few outlying Ifẹ̀ suburbs were involved in some of the stages of glass and glass bead production. Our archaeological excavations in Osogbo and Ede-Ile, conducted since 2011, have revealed glass crucibles and cullet, providing evidence of glass processing from the 17th to the 18th centuries.

The mastery of primary glass production technology was a watershed in the history of Ilé-Ifẹ̀ and the Yoruba world. The number of divine kings proliferated throughout the region between the 12th and 14th centuries, partly because the instruments for legitimising these offices were accessible from Ilé-Ifẹ̀.

As the dispenser of the instruments of divine kingship and wealth, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ used this technological advantage to incorporate a vast area under its political, hegemonic, and economic orbits and create a new regional identity. This is the only case of what resembles “technological sovereignty” that we know so far in early West Africa, if not in the whole of Africa.

In contemporary terms, “technological sovereignty” is the use of particular technological innovations and preferences “to forge national identity, competitive advantages in the global economy, national economic growth, and global connectedness” (e.g., steel in the US, the British cotton textiles of the Industrial Revolution, and Japanese consumer electronics). In this case, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ used glass technology to bolster its local economy and foster a new pan-regional identity. This advantage of knowledge capital (in glass bead production) promoted the status of Ilé-Ifẹ̀ as the guarantor of social order, expanded the city’s network of client polities, and transformed it into an emporium.

These glass products were traded far and near. Using LA-ICP-MS and SEM-EDS (Scanning Electron Microscope With Energy Dispersive Spectrometry), we now know that Ife glass beads have a unique chemical signature, which Lankton, Ige, and Rehren called HLHA glass, and which I have renamed Yoruba Glass. Beads of this chemical signature have been found in different parts of the Yoruba-Edo region dating to the 13th through 18th centuries, from the suburbs of the Ifẹ̀ metropolis (e.g., Òṣogbo, Ẹdẹ-Ilé, Iléṣà, and Ìlàrè) to the client states in Ife’s outlying spheres of influence, including Ọ̀wọ̀ and Benin in the east, and Ṣábé (Savé) in the west. These dichroic bluish, greenish, and yellowish beads with HLHA chemical properties have also been identified farther afield, from Igbo-Ukwu in Southeastern Nigeria and Birnin Lafiya in Northeast Benin Republic to Kissi in Burkina Faso, Diouboye in Senegal, Gao Ancien and Essouk in Mali, and Koumbi Saleh in Mauritania, all dating to the 11th through the 14th Century.

Principle Abundance As The Basis Of Yoruba Cosmopolitanism

The name “Ilé-Ifẹ̀” means “House of Abundance” or “House of Expansion.” Not “House of Love,” as folk etymologies tend to suggest. In Yorùbá ontology, a place expands based on the number of people it can contain and the opportunities available. The size of a place is defined, not by its physical size, but by the number of people who live there, its openness to visitors, and its diversity. Of course, a place with abundant resources—food, wealth, jobs, and opportunities for social mobility — will attract many people. Therefore, it will be an expanding place or a place of abundance. This people-centric conceptualisation of space, in both bodily and cosmopolitan terms, is the foundation of Yorùbá sociology of urbanism.

Ilé-Ifẹ̀’s name, as Professor Rowland Abiodun noted, evokes “a society that was not only . . . prosperous and progressive but also stable and welcoming to indigenes and non-indigenes alike…” The facial marks and sartorial features represented on some of the classical Ifẹ̀ terracotta figures suggest these foreign origins and demonstrate that Ile-Ife offered opportunities for social mobility, being a place where social diversity and cultural differences were celebrated.

More Than A Ritual Centre: Ile-Ife Created The First And Most Lasting Empire In Yoruba History

An empire is a territorially expansive and incorporative state that exercises political, economic, spiritual, and ideological control and influence over several other political entities, including city-states, kingdoms, and village polities. Based on my archaeological and historical research across Yorubaland, I concluded, about seven years ago, that Oyo was not the first or only empire in Yoruba History. There was an earlier Ife Empire that controlled a large part of the Yoruba region from ca. 1200 to 1420, economically, politically, and culturally.

Let me begin with the economy: Ilé-Ifẹ̀ employed military and diplomatic strategies to open and protect the trade routes to the River Niger, especially between Moshi and Oṣìn tributaries. Ifọ́n was one of these Ifẹ̀ colonies. Located in the upper reaches of Ògùn River between Sepeteri and Igbeti, the colony is described in the oral traditions as a prosperous trading town where an assortment of Ifẹ̀ glass beads was bought and sold. Ifọ́n was part of the network of other market towns in the region, such as the famed Èjìgbòmekùn. One panegyric of Ifọ́n goes thus:

It is the patron deity of commerce that established Ifọ́n

There are four markets that Ọbatálá founded in Ifọ́n

Today, I attend the ṣẹ̀gi market

Tomorrow, I will go to the iyùn market

In two days, I will visit the white-bead market

Who is going to the House of Olúfón?

Greet Ọbatálá for me

Who is going to Èjìgbòmẹkùn?

Greet Òòsàtàlàbí for me

The child of Èjìgbòmekùn

Greet Ọlọ́pọ̀ndá

The child of Alágbàá in Ifọ́n

Ilé-Ifẹ̀ created colonies and transformed some of the contemporary polities into client states, some for political reasons and others for economic purposes, mostly to protect its commercial routes. Two of these prominent client states were Òwu and Ọ̀yọ́, close to the River Niger. They control the land trade routes linking the Yorùbá World to Western Sudan. In the south-east, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ propped up Ọ̀wọ̀ and Benin kingdoms as client states.

The Ìta Ìjerò and Ọ̀rànmíyàn legends, so popular in Yorùbá and Benin traditions, are revealing of Ilé-Ifẹ̀ as an expansionist territorial state. The Ìta-Ìjerò legend tells the story of the conference that royal brothers, cousins, and nephews held in Ilé-Ifẹ̀ soon after the creation of the city-state. The purpose of the allegorical meeting was to arrive at an orderly process by which each participant would leave the city to replicate elsewhere the model of governance that their patriarch, the mythic Odùduwà, had established. Before departing to establish their respective kingdoms, they promised to stay in touch and support one another in times of trouble. The Ita Ijero saga is an allegory that invites critical historical analysis. It is not to be read literally.

The Oranmiyan legend is about a charming and roving Ifẹ̀ prince, diplomat, and warrior who won many battles and forged numerous diplomatic charters. He was also successful in siring many princes with indigenous women in several places, including Ọ̀yọ́, Benin, Òkò, and Àkúrẹ́, where his sons became the founders of Ifẹ̀-centric dynasties. The marriage of Ọ̀rànmíyàn to a Nupe princess and daughter of a Benin nobleman, for example, is a stock narrative to legitimise the incorporation of Oyo and Benin into the Ife Empire through conquest and diplomacy.

Ilé-Ifẹ̀ used its glass technology to standardise the political ideology of the divine kingship and create dependencies across the region. However, it was also a military power that used the whip when necessary and the carrot when affordable. Ilé-Ifẹ̀ did something else that was characteristic of all hegemonic states and empires in world history. It transformed itself into the holy ground for the Orisa religion, the place where the universe began, and to which all its creation would return. Hence, people who were far-flung and belonged to different hierarchies of power and positionality came to see themselves as belonging to the same community.

By transforming itself into a referential place, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ was reconfigured into a centre of learning (of the Òrìṣà ways), and a place of memory-making and pilgrimage. Different Òrìṣà schools dotted the landscape of the ancient city, attracting students and teachers from far and near. Its sacred sites, commemorative cenotaphs, and elaborate Òrìṣà festivals also drew in pilgrims every season. The temples of these deities were sites of spectacular ceremonies and rituals. All of these, as well as the splendor of the kingship institution and fabulous wealth of the city, brought “pilgrims, ambassadors, and political emissaries, as well as ambitious young people, labourers, fortune seekers, and entrepreneurs to the city” (Ogundiran 2020: 137).

Ancient Ile-Ife was also a centre of learning in all branches of science and arts, including philosophy, material chemistry, Ifa divination, and astronomy. This Yoruba city was a contemporary of other intellectual cities in the world, such as Oxford and Cambridge in the United Kingdom and Timbuktu in present-day Mali. Ife, Kanem, and Mali Empires anchored the political landscape of West Africa between 1200 and 1420, and all three collapsed in the early 15th Century.

Collapse

The regional economic integration that Ilé-ifẹ̀ anchored in the Western Lower Niger began to unravel around 1380, and by 1420, the ancient city was only a shell of its former self. The empire as a political entity came to an end, and the Yoruba World was in disarray. This collapse originated from three sources:

First, there were political intrigues in the metropolis and frontiers of the Ife Empire during the late 14th Century that weakened the central government. I also argue in my book, The Yoruba: A New History, that the overproduction of glass beads reduced the purchasing power of the commodity in the regional market. The result was a collapse of Ilé-Ifè’s economy between 1380 and 1420.

Second, the onset of cyclical episodes of severe drought at the subcontinental level, the southern hemisphere’s equivalent of the Little Ice Age, caused distress for many communities. This climate-related distress, along with the consequences of famine, hunger, and displacement, created conditions for political instability and fragmentation, brigandage, and conflict. It was also associated with the outbursts of endemic and epidemic diseases, especially smallpox and possibly respiratory illnesses, which worsened the ecological distress and led to many deaths over a period of 40 years.

The internal political crisis and hemispheric ecological trouble were worsened by external events that were also responding to their own political and ecological problems.

These external troubles came from two directions—the Nupe-Hausa-Kanem axis in Central Sudan and the Songhai axis in Western Sudan.

Nupe Brigandage

As political instability and the effects of ecological crisis were ravaging the Yoruba World, external attacks in the form of brigandage by the Nupe cavalry men crossed the Niger River into Yoruba country in search of captives whom they sold primarily to Central Sudan in exchange for horses. As a result, many Yoruba communities and kingdoms, from River Moshi to the Niger-Benue Confluence, were depopulated and evacuated. The first Oyo Kingdom was a casualty of Nupe brigandage, forcing the kingdom’s leaders to settle farther south in present-day Igboho.

The Songhai Crisis

The second source of external instability for the Yoruba World was Songhai:

Songhai’s incessant bloody succession disputes and seemingly endless internal strife between different factions of the elite affected all its neighbours as refugees from these wars spilled over to the adjacent areas, especially among the Mossi and Ibariba in the south and Hausa in the east. According to Michael Gomez, the Songhay aristocrats were also interested in these areas as sources of captives on their agricultural plantations, the first of such large-scale farmlands in West Africa.

The Islamisation of social life and government, initiated by Askia Mohammed in 1493, unleashed a blood bath between the Songhay Muslims and non-Muslims, leading to the death and exile of several followers of his predecessor, Sunni Ali, who was pro-Indigenous Religion. Thousands of those exiles moved south into the Mossi, Ibariba, and Yoruba territories. A question that has been missing in the historiography is how Songhai’s neighbours—the Mossi, the Ibariba, the Northern Yoruba, and other groups responded to this Islamisation project and ideology of enslavement.

Strategies Of Recovery: Regional Multi-Ethnic Coalition

I think I have the answer. From their base in Ìgbòho, the Òyó monarchs built the first and largest regional and multiethnic military coalition in West African history. The alliance included the Mossi, Ìbàrìbá, Wasangari, Wangarawa, and Djerma—a branch of the Songhay opposed to the fundamentalist tendencies of Askia Mohammend and his successors. Each group had different priorities, motives, and roles in the coalition. Some were independent mercenaries and merchants, and others were state-sponsored. All were nursing the wounds from either the Nupe brigandage or the Songhai aggression and Islamisation policy. However, the Oyo built this coalition primarily to expel the Nupe from their homeland and rebuild their kingdom.

In the savanna landscape where the Òyó-Ìbàrìbá-Mossi-Wasangari coalition was planning their showdown with the Nupe, a cavalry force was a necessity. The Djerma, Mossi, and Wangarawa provided the Oyo with the horses and also provided the training. Soon, the coalition began to downgrade Nupe’s militarist power in a series of battles fought in the second half of the 15th Century and, by 1570, Nupe was brought under the control of Oyo. This success marked the beginning of Oyo’s recovery from the 150-year political instability in the Yoruba region.

I also refer to this period as six generations of silence and memory loss in Yoruba historiography. But thanks to archaeology, oral traditions, and ritual archives, we are finally filling this gap. The Oyo consolidated their military gains by establishing a new capital at Oyo-Ile. With this, they laid the foundation for what would become the Oyo Empire, West Africa’s largest political formation, south of the River Niger, between 1600 and 1817. Many non-Yoruba leaders of the coalition and their followers also settled in Oyo-Ile and were rewarded with political offices. For example, the office of Basorun, the second most important title after the king (Alaafin), went to the Ibariba and Mossi leaders of the coalition. They became Oyo citizens and, by extension, assumed Yoruba identity while also keeping their ancestral Ibariba and Mossi identities. The Ibariba-Mossi Coalition adopted Ogun as their primary deity, while the Alaafin adopted Sango, also known as Jakuta.

The facial marks prevalent among the Oyo-Yoruba, such as gọ̀m̀bọ́, máńdè, and jáńgbadì, and the family histories of many chieftains and dynasties in the old Oyo provinces, are tell-tale signs of the multi-ethnic origins and compositional nature of the empire and the metropolis. Here, the multicultural composition that shaped the history of Oyo-Ile followed the same pattern as that of Ile-Ife.

Third Case: Osun Grove: Suzanne Wenger Effect

Nigeria has two World Heritage sites. One of them is Osun-Osogbo Grove. I have been working on the landscape and cultural history of the grove for some time, and one dimension of the research involves how the grove’s landscape resources were used as intercultural communication between the Austrian-born artist, Susanne Wenger, and the Osun priestesses/priests in Osogbo.

Susanne Wenger settled in Osogbo in 1958 and remained there for the rest of her life (died 2009). She was a local priestess and spearheaded the most important grassroots-based cultural revival in modern Yoruba History. The collaboration between her and the indigenous community created a new experience for Osun Grove.

Between 1960 and 1995, Wenger was in intense dialogue and debates with different Osogbo constituencies. Some antagonised her ideas, and others collaborated with her. Wenger and her collaborators created an artistic movement known as the New Sacred Art School, a collective of artists working in expressive individualistic styles. For over 40 years, the artists have populated the grove with more than ninety cement and wood sculptures representing various Yoruba deities and myth-historical events. By so doing, they created what I call a “Yoruba cosmological city” in the Osun Grove. This “cosmological city” is organically laid out based on the extant community’s multi-layered historical memory and a conceptual framework that fuses Jungian theory of the collective unconscious (à la Wenger) with the Yoruba ontology of cultural experimentation. Wenger became Yoruba, not an ethnic Yoruba but an epistemological Yoruba. She was a priest of Obaluaye (Sonpona) and was inducted into the Ogboni Fraternity, the most revered indigeneity organisation in Yoruba History.

Since the 13th Century, if not before, the Ogboni or Osugbo have served the purpose of integrating foreigners into the host community, transforming them into citizens, while also protecting the interests of the indigenes. This institution played a crucial role in managing differences within Yoruba political spaces and ensuring that the interests of foreigners did not supersede those of the indigenous population. The Ogboni is averse to foreigners lording their will over the indigenous people.

Let me remind us that the Ogboni played a major role in the underground resistance that liberated the Egba from the Oyo Empire’s domination in 1780. It is telling that the British colonial government and its Anglican Church agents mounted a vigorous campaign of disinformation against the Ogboni, forcing its members to go underground during Colonial Rule. Thanks to our colonial education, this potential agent of our liberation and defense is now seen by many of us as the genesis of our problem. The British were wiser than we are. They knew that the Ogboni must be driven underground for their colonial agenda to be successful. Our historiography will continue to be impoverished until we develop the methods for studying the deep-time history of such institutions as the Ogboni, so we can better understand the purposes they served in the past and what may be their relevance today.

Nation State As Tribal and Totalitarian

In his book, The Ends of Globalization (2000), Mohammed A. Bamyeh describes the nation-state as a totalitarian form of political formation, irrespective of whether the form of governance in a given country is democratic or dictatorial. The modern state claims to stand for and act on behalf of horizontal solidarity-the “people,” the “nation.” Yet, with a few exceptions (e.g., South Africa), these nations tend to recognise only one language, one religion, and one culture, and one identity. Any other form of identity is viewed as inferior to the nation-state. Unlike the Yoruba cosmopolitan epistemology that I described at the beginning of my presentation, the nation-states are neither organic nor emergent. Instead, they are deterministic and homogenising, and tend to be intolerant of differences, especially cultural plurality. For the nation to function, its creators must transform the diverse cultures they incorporated into distinct tribes or ethnicities. This should not surprise us.

The European countries that brought the idea of nation to the Global South were highly tribalised, racist, and genocidal within their own borders. The genocidal impulse of the British, Dutch, Portuguese, French, German, and Belgian led to the displacement of millions of people from their ancestral land and the death of hundreds of thousands from East Africa to Southern Africa between 1890 and 1944. The German Nation spearheaded the Holocaust that killed millions of Jews and half a million Jehovah’s Witnesses, Roma (Gypsies), homosexuals, and people with disabilities. The quest to maintain the fictive German pure blood led to the sterilisation of mixed-race children, especially of Black and German parentage.

According to Etienne Balibar, for the nation-state to exist, it must invent “fictive ethnicities” or “fictive tribes.” The irony must be evident by now that the pre-colonial cosmopolitans became a tribe once they were incorporated into colonial and postcolonial Nigeria.

The Yoruba are not the only fictive tribe within the Nigerian nation-state. But the problem is compounded because the concept of compositional and multipolar identity, so central to Yoruba identity, is not shared by everyone incorporated into the Nigerian State. The nation forces everyone to pick only one ethnicity. With the emergence of the colonial nation, it is no longer possible to be Nupe and Yoruba at the same time, or to be a Baatonu and Yoruba, or Edo and Ife based on mutual respect for every part you claim. You must pick a side. I understand this is a controversial issue, but I urge scholars not to run away from it but to critically interrogate the challenges that this scenario presents to our communities and the future of the postcolonial state.

Indigeneity matters. It mattered in the Ife Empire and the Oyo Empire. It matters in present-day Osogbo. It also matters in the nation-state. Indigeneity is tied to land, language, culture, and history, but it is also a network of people and individuals who subscribe to the same philosophy of life, ontology, and epistemology. This is what makes it possible for a white Austrian or a mixed-race Brazilian to be Yoruba by virtue of practicing the Yoruba religion. But not all ethnic Yoruba within Nigeria practice the Òrìsà religion. In order to transcend this conundrum, we should stop referring to the Yoruba as a tribe or ethnicity. The Yoruba are more than any of these.

Rather, we should begin to recognise the Yoruba as a community of practice in order to retain the qualities of its compositionality, open-endedness, flexibility, and elasticity in ways that transcend Nigerian boundaries and speak to our aspiration for a better future.

Conclusion

Most academic historians are in the public space. But we have been hesitant to deploy the tools of critical historical thinking and deep-time perspective to inform controversies and national issues that involve cultural identity in Nigeria. I recognise that we face three challenges: first, we have the legion of social media influencers who also double as armchair historians—highly opinionated, irascible, and quick to abuse; second, there are well-meaning citizens and intellectuals who understand the logic of critical thinking but are poorly equipped with critical historical thinking and cannot decipher the difference between history and fable or allegory and history; third, we are confronted with the challenges of Artificial Intelligence (AI and Google.

Who is an academic historian? This is a person for whom historical inquiry is a profession and vocation, often with a teaching position. Academic historians utilise primary sources, which include documents, eyewitness accounts, oral traditions, language forms and linguistics, archaeological artifacts, and material culture, to write history. They also use performative arts such as music, dance, and rituals as sources. They ask questions of what, why, how, where, and when, and are attentive to the six Cs of historical thinking: context, change, continuity, causality, complexity, and contingency. When done well, their work is different from hagiography–an adulatory, idealised, and uncritical story about a place, time, or person.

Unfortunately, it seems most Nigerians don’t know the difference between academic history and hagiography or amateur history. I can therefore understand why some of us devoted to the historian’s craft and spend enormous time and resources excavating and interpreting that past with primary sources are often exasperated by the pronouncements and writings that we encounter on social media, and which some of our elites parrot as gospel truth. Such falsehoods and illogical stories are causing significant harm to the general public, particularly to younger people.

Therefore, I call on historians to embrace their roles as custodians of the past. The same way it will be absurd to trust the President of Nigeria to serve as the custodian of Nigerian History, it is also absurd to entrust a king as the custodian of ancestral history. They have political interests that we must interrogate, and I am aware of any town in Yorubaland where the Palace is the only repository of history. Every lineage, every Orisa temple has its history. The history of a town or past kingdom is shared by different constituencies.

We expect our royal fathers to invest resources in preserving ancestral legacies, artifacts, and memory. If they are committed to the truth and not self-aggrandizing, they should build museums and establish royal and ritual archives in their communities. These are the resources that historians need to do their work effectively. We must be deferent to our kings, but we must reject royal rascality. We expect our kings to move with pomp and circumstance, but we must reject pomposity and arrogance from them. We must not allow egocentric fables to be mistaken for facts. Yoruba History is bigger than the ego of any royal father. If the kingmakers will not check them, we owe it to our profession as historians to call them out through our professional organisations.

To this end, I propose that a Council on Yoruba Historical Studies be established to take on the responsibility of organising historical retreats for our leaders, including our princes and princesses, kingmakers, chiefs, and kings, and fact-checking misleading historical pronouncements they might make in public. The Council’s intervention must be based on established evidence and references to relevant literature. The Council must be humble to admit what we don’t know and guide in pointing to areas of new research.

I particularly call on the Development Agenda for Western Nigeria (DAWN) Commission to take the lead in this endeavor. There can be no development without an evidence-based history. I admit that historical narratives are always being contested and revised, but such revisions must be based on new evidence and theoretical insight, not on an individual’s whims and caprices. Likewise, I call on our Departments of History across Nigeria to rethink their approaches to historical education. A curriculum that focuses primarily on colonial and postcolonial history can only impoverish the intellect of future generations. I have said this many times, and I will say it again. We need a closer curriculum alignment among departments whose intellectual frameworks are based on historical thinking, such as archaeology, anthropology, Classics, Art History, and History.

Thank you for coming and thank you for listening.

•Faculty Distinguished Alumnus Lecture, Faculty of Arts, University of Ibadan, Delivered by Professor Ogundiran, FNAL, FAAN, FSA, Cardiss Collins Professor of Arts and Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston, USA, September 2, 2025.