How was I to know that that meeting I had with the Alaafin of Oyo, Oba Lamidi Adeyemi, on March 2, 2022, was the last between a father and his son?

In the last couple of hours of hearing of his passing, I have scrutinized, without success, memories of anything unusual in the sky on that day that probably spoke of the looming calamity that would befall the Oyo Palace.

The sky was the usual grey, without a foreboding countenance; the palace courtiers were the usual ensemble, spraying entrants with deodorant courtesies. The palace bard perhaps gave inkling of the queer day.

His effusion of praise songs for me on this day was unusual: “Adedayo, mo wole, awo Alowolodu…” he chanted his welcome endlessly in a poetic cadence that is the stuff of Yoruba palaces. Aside this, there were no tell-tale signs for me to ferret any inkling that this was the last time I would be seeing Oba Adeyemi alive, in a palace I had visited for over two decades.

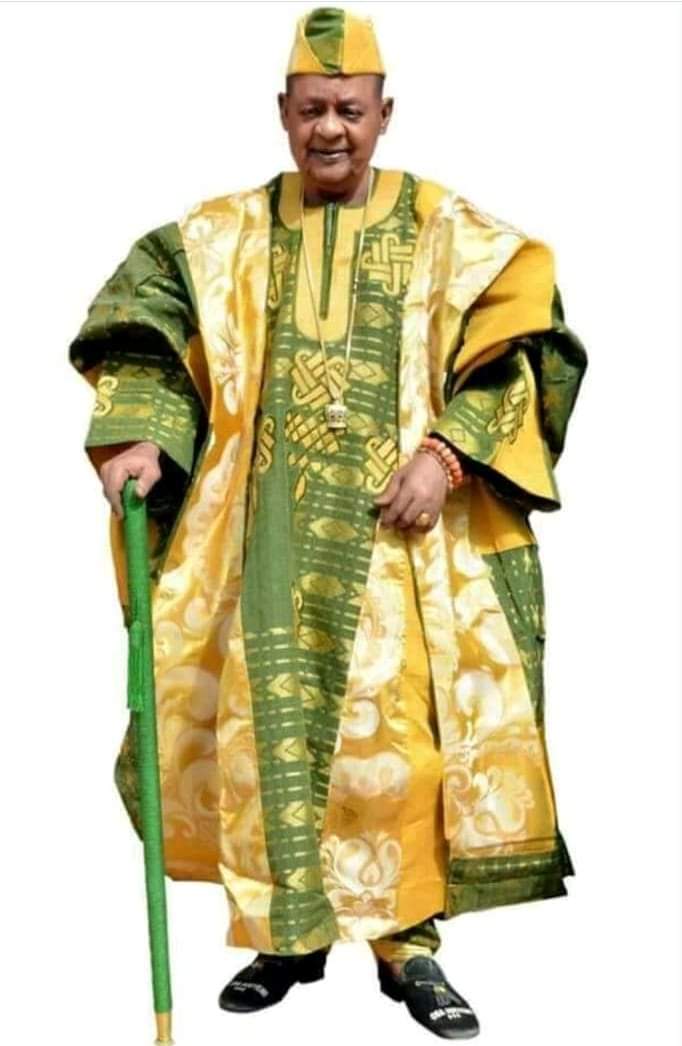

The Alaafin sat in his regal best on this day. A highly sartorially conscious monarch, each time you saw the Alaafin, he mirrored class and the panache of culture in his dressing. He was dressed in a blue ankara, done in agbada, with an abetiaja cap to match and a slip-on pair of shoes as a fitting accoutrement.

With me was ace broadcaster, Yemi Sonde, ex-Broadcasting Corporation of Oyo State (BCOS) broadcaster, Bunmi Labiyi and another female guest. We had gone to invite the foremost monarch to the official commissioning of Sonde’s new radio station in Ibadan, Oyo State.

As usual, as the glass door was pulled aside for us to enter Kabiyesi’s inner sacristy, the men went on all fours and the female, on their knees. As it is the tradition in the palace, we had peeled our feet of our shoes at the main entrance.

From the blues, Kabiyesi veered into the conversation of death. His grouse was with the recently promulgated Ogun State Traditional Rulers (Installation and Burial Rites) Act which had by then just scaled second reading in the State House of Assembly.

In the Act, which claimed to be bothered about the need for respect for human dignity and promotion of modernity in the installation and burial of traditional rulers, lawmakers proposed a legal framework that was to curb idolatry practices in installation, as well as burial of traditional rulers. The purport of the Act was to guide jealously the religious beliefs of a deceased monarch in Ogun State, by according them burial rites contiguous with their belief and religion.

In Yorubaland, though an issue that was a taboo scarcely discussed, it is a notorious fact that upon the demise of a deceased oba, traditional worshippers hijack obas’ corpses from their families, superintending solely on the burial rites, which included gouging out their hearts, which were preserved to be fed to their successor.

Oba Adeyemi told me he had conveyed his disagreement to the law to his colleague Oba, the Awujale of Ijebuland, Oba Sikiru Adetona, the monarch he had tremendous reverence for. The law didn’t make any sense, he said.

“Why would a state government be bothered about the burial rites of a king?” he asked, incredulous. “When the man dies, he doesn’t know what is done after his departure. He is gone; whether they remove his body parts or not. In my own case, I have picked the place where I will be buried in the palace. At my age, I am already at the departure lounge. The plane is on the ground and I am just waiting for the boarding pass. The Oyomesi know what to do with my corpse and they will do it.”

Alaafin was however not happy with how the corpse of the immediate past Olubadan of Ibadan was on display on social media and commended the example of the Soun of Ogbomoso’s burial which was made a strictly palace affair. I don’t know how Baba would feel yesterday seeing his priced remains floating on social media in the hands of clerics.

Alaafin was a federalist to the core. He canvassed Nigeria’s practice of federalism till his last day on earth. He was also one of those who believed that the 1914 Lugardian amalgamation was a disaster to the wellbeing of Nigeria. His forebear, Oba Ladigbolu 1, he said, told the colonialists to their face that, by soldering unlike people together to form a single whole, what Britain was doing was analogous to fostering the lion, impala and other preys together in a common zoo. Which is a reflection of the Yoruba people’s travails in the Nigerian pseudo federalism.

Veteran journalist and ex-Tribune’s Political Editor, Baba Agboola Sanni, took me to the Alaafin in 1998 or thereabout and since then, our relationship was akin to father and son’s. To example the level of the relationship, in 2020, Oba Adeyemi had invited late rights activist, Yinka Odumakin and me to his palace. It was when we got to the palace that we realised that we had been individually invited for the meeting. It was a Sunday.

Hyper-passionate about the fate and lot of the Yoruba people, Alaafin called us to discuss nagging Yoruba national issues, chief of which was the invasion of Fulani herders of the South-West and the kidnapping and killings that had become commonplace. After the meeting, in his usual sotto voce, Alaafin faced Odumakin and said, “In this palace, Festus and I have fought several battles. We never lost one.”

Odumakin looked at me. I looked away. He apparently could not match what he just heard with the person sitting beside him. When ace Tribune columnist, Dr. Lasisi Olagunju, eventually met him in the palace, pointing at me, he repeated the same line.

In the passing of the Alaafin, I wish the Yoruba knew the calamity that had just befallen them. Yoruba are naked, more than ever before, to their bare skins, in the hands of forest demons and reptiles who bay for blood.

I have had opportunities of meeting monarchs in my few years on earth and interrogating their commitments and dedication to the land, but none-apologies to no one–answered to the tripartite calling of kingship–armour-bearer of their people, cultural icon and language encyclopedia–that Alaafin personified. Majority of them are scammers in search of green grass to pillage and who are bereft of the avant-garde role the ancestors have in store for them.

Alaafin loved Yoruba to the level of incurable obsession and lamented the regression of the people’s fate in the hands of Nigeria and her slavish rulers. Unbeknown to many, Alaafin, to my knowledge, invested millions of his personal funds in fighting the enemies of Yorubaland, at the risk of his person and office. He made files of these interventions, copies of which he handed over to me, apparently mindful of a today.

For reason(s) that I still find difficult to decode, which perhaps I will have insight into at a later tete-a-tete with him in the hereafter, Alaafin confided topnotch secrets in me and believed in the ability of a resolution to any difficult impasse once he and I gave it a mental interrogation.

He would call me early in the morning to ask for my convenience and would set out from the ancient town of Oyo and drive to Ibadan. His Idi-Ishin, Jericho Quarters apartment offered a convenient ground for granular chewing of challenges that he might need resolution to. Once we were done, he would head back to his palace, telling me that it was the only reason why he had come.

Alaafin got attracted to cerebral people like bees do hives. He worshipped Professor Wole Soyinka like a god and venerated Prof Adebayo Williams. Along the line, Kabiyesi got inebriated with the intellectual depth of Dr. Olagunju too and asked that he be brought to the palace. Since then, Alaafin never hid his fascination with Olagunju’s weekly mental contributions.

“Whenever I go to functions, I would deploy a medley of Olagunju, Adebayo Williams and Adedayo’s works and pontificate with them in the public,” he said in a rare humility from a foremost monarch with a first class brain. He also said that now that he had the Eripa-born media intellectual, Olagunju, his artillery had increased. When Olagunju and I went to the palace to invite him to the launch of his book, Cowries of Blood, and he knelt to hand Alaafin a letter of invitation, the monarch prayed so intently for him that you would think it was a father’s last minute prayers for his son.

Alaafin was in the know of every of Sunday Igboho’s movements and war against haters of the Yoruba people and provided pieces of advice to him on how to fight his traducers. He called him many times in my presence. He never hid his resolve to protect Yoruba people and cleanse their forests of invaders, particularly Oke-Ogun and Ibarapaland of Oyo State.

Alaafin had challenges with Governors Lam Adesina, Rasidi Ladoja and Adebayo Alao-Akala. He gave me the most granular information of the roles he performed in the tiffs with these governors.

By 2015, especially the moment leading to the general election, Alaafin and Governor Abiola Ajimobi’s relationship had gone sour. Goodluck Jonathan had begun to make overtures to traditional rulers. Ajimobi had gone to the UK when Alaafin called me, demanding that we had a mutual resolve on where he was heading politically. I called Governor Ajimobi to intimate him of Alaafin’s quest, careful to beat the possibility of tale-bearers parroting my “clandestine” visit to the palace to him. Ajimobi gave me the go-ahead to meet the monarch.

At the meeting in the palace, Alaafin articulated his coterie of grouses against Ajimobi to me. He told me that, in company with his late friend, Azeez Arisekola-Alao, he launched one of the most penetrating artilleries against Alao-Akala, even selling his house in the UK in the process. Ajimobi, he alleged, took all these for granted and never reciprocated the gesture.

When it was time to address him, I prostrated. I told him that my loyalty was to him, as it was to Ajimobi, but I owed him the need to tell the absolute truth. I told Alaafin that Ajimobi had the greatest regard for him. I proceeded further to tell the king that the governor, at many fora, told me that, but for Alaafin, he wouldn’t probably have emerged governor in 2011. Alaafin went beyond the ken of his traditional role in his support for Ajimobi in 2011, so much that if Alao-Akala had won that election, he would have deposed him, so said Ajimobi to me which he expressed as, “Alaafin taa tan ni!”

I reminded Alaafin that I was privy to conversations between the king and his aides–Late Prince Fehintola and Hon Kamil–during the 2011 elections when, at the thick of the announcement of the gubernatorial results and he wasn’t sure where the pendulum was swinging, he asked his aides to tell him the truth, giving them indications that he could commit suicide, if Alao-Akala won.

“Kabiyesi, you are the king of the Yoruba people, you cannot work against your people, both at the state and national level” I concluded. That settled the matter between Alaafin and Ajimobi. From that moment on, they became the best of friends.

Alaafin, despite his average schooling, was a profound intellectual. He could flawlessly recite by rote speeches read by foremost politicians of the First Republic, especially S. L. Akintola’s. During our last meeting in the palace where he articulated some legal permutations, I reminded him of how I always called him the SAN that we never had.

Perhaps due to the several litigations he was involved in and his quest to apprise himself with details of judicial decisions, Alaafin gobbled up knowledge of law that was non-pareil. He was a restless fighter who sought for war in a time of peace. Once, Professor Wale Adebanwi had taken University of Cambridge’s Africanist scholar, Prof D. Y. Peel, to the palace. At discussion, Alaafin arrested Peel with his flawless rendition of British history, so much that Peel shouted, “Kabiyesi, you are telling me my history!

In 2019 again, it was time to pitch his tent with a gubernatorial candidate in Oyo State. Alaafin invited me from Lagos where I was a student of the Nigerian Law School. He then took me to a section of the palace that I had never been to before. Donning his pyjamas that morning, he confided in me that he had made his personal investigations and concluded that Seyi Makinde would win the election and he was ready to support him. I was shocked to learn thereafter that some persons persuaded him otherwise. It affected his relationship with the governor, which he lamented, till his death.

In my over two decades of relationship with the Alaafin, the testimonial that I always wear on my lapel was given me by his first son, Aremo, about five years ago. It was a Sunday as well. Alaafin had asked me to meet him in the palace. On getting there, I called him on phone that I was waiting in the waiting hall. A few minutes after, palace courtiers asked me to advance to Kabiyesi’s sitting room. There, I met the Alaafin, his first son called Aremo in Yorubaland and the Aremo’s wife, then a Magistrate in an Oyo court, sitting in wait.

As I sat, the Aremo pointed at me and said: “Whatever you do for my father that earns you the kind of respect and midas touch you have on him, please keep it up. I lived here in the palace as a young boy and I understand the tone and tenor of every of Kabiyesi’s answers to his being told of the presence of his guests. ‘Aa ri, mo nbo, o da’ were suggestive of several of his dispositions and palace courtiers understood what each of them meant. This evening, immediately he learnt of your presence, he said, ‘let us leave immediately; I cannot keep Festus waiting!’ That, to me, means a lot,” the Aremo told me.

From where I sat, I looked into Kabiyesi’s face. What I beheld, for the very first time, was a coy-looking Kabiyesi, a childlike smile glued to his face, looking at his tangled fingers. His son had apparently shot at his Achilles heels.

The tragedy of Alaafin’s passing for the Yoruba is immense. Of all their obas, none had Kabiyesi’s stubbornness, mental alacrity, patriotism, panache and native intelligence to fight the battle of the people’s appropriate positioning in the national scheme of things. He often joked of how Kabiyesi Olubuse, the late Ooni of Ife, would tell people that he could not withstand Alaafin’s stubbornness.

While others go cap in hand to pick crumbs from Yoruba enemies, Alaafin was too proud of the numero uno Yoruba stool he sat on to subject it to the whims of Yoruba suppressors. No Yoruba oba living possessed Alaafin’s brilliance, commitment and love for the Yoruba people; perhaps next to him is the Orangun of Oke-Ila, Oba Dokun Abolarin.

Alaafin never suffered fools gladly and would stand by his Yoruba people, no matter the persuasions to do otherwise. In our last meeting at the Jericho Quarters, we both agreed that he should embark on a diplomatic shuttle among his colleague obas on who the Yoruba should support for the 2023 presidential election. He was to embark on this shuttle, first to the palace of the Awujale, and then to others’. I told the Alaafin who I felt Yoruba should not support, neglecting to suggest who the Yoruba should queue behind. He seemed to agree with me. Though he never told me in unmistakable language, I could hazard a guess the Yoruba man he would have supported.

Alaafin was one of the most brilliant men I knew. Imbued with native intelligence and articulation that was borne of his inebriation of self in reading and gathering of knowledge, while men slept, Alaafin was in his library. He was a step ahead of his traducers mentally, steeping himself in intellectual exercises at every opportunity.

One day, at about 8am on a Sunday, I told some friends that Alaafin must have read the day’s dailies but they disputed my claim. When I called him and put the phone on speaker, he analyzed what I wrote in the day’s newspaper and all the issues on display in the public sphere.

Alaafin was also very principled and followed all the laid-down ancient precepts of the traditional Yoruba monarchy. He would never eat in public and abhorred alcohol. His meal was amala, eko and other foods he inherited from his forebears. He frowned at the emerging crop of obas who were bereft of the mental and physical insignia of a king and who got themselves polluted with modern fripperies.

As I write this, I confess that the full implication of Alaafin’s death hasn’t dawned on me. I am yet to internalise the eternal truth that I will never see my father, the Alaafin of Oyo, again.

An apt analogy that can explain Oba Adeyemi’s passing is a huge library burnt down. Another is a fitting analogy that Ayinla Omowura gave in description of the sudden passing of his brother, composer and friend, Akanni Fatai, also known as Bolodeoku, which he labeled, agboju’gbanu. Alaafin’s passing is an agboju’gbanu, a jolting news heard that provokes the sudden fall of the calabash held in one’s hand.